Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture

| Prove or disprove Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture. |

In theoretical computer science, the Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture (also known as the Aanderaa–Rosenberg conjecture or the evasiveness conjecture) is a group of related conjectures about the number of questions of the form "Is there an edge between vertex u and vertex v?" that have to be answered to determine whether or not an undirected graph has a particular property such as planarity or bipartiteness. They are named after Stål Aanderaa, Richard M. Karp, and Arnold L. Rosenberg. According to the conjecture, for a wide class of properties, it is not possible to skip any questions: an algorithm for determining whether the graph has the property must examine every pair of vertices. A property satisfying this conjecture is called evasive.

More precisely, the Aanderaa–Rosenberg conjecture states that any deterministic algorithm must test at least a constant fraction of all possible pairs of vertices, in the worst case, to determine any non-trivial monotone graph property; in this context, a property is monotone if it remains true when edges are added (so planarity is not monotone, but non-planarity is monotone). A stronger version of this conjecture, called the evasiveness conjecture or the Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture, states that exactly n(n − 1)/2 tests are needed. Versions of the problem for randomized algorithms and quantum algorithms have also been formulated and studied.

The deterministic Aanderaa–Rosenberg conjecture was proven by Rivest & Vuillemin (1975), but the stronger Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture remains unproven; this problem has been open for close to 35 years. Additionally, there is a large gap between the conjectured lower bound and the best proven lower bound for randomized and quantum query complexity.

Contents |

Example

The property of being non-empty (that is, having at least one edge) is monotone, because adding another edge to a non-empty graph produces another non-empty graph. There is a simple algorithm for testing whether a graph is non-empty: loop through all of the pairs of vertices, testing whether each pair is connected by an edge. If an edge is ever found in this way, break out of the loop, and report that the graph is non-empty, and if the loop completes without finding any edges, then report that the graph is empty. On some graphs (for instance the complete graphs) this algorithm will terminate quickly, without testing every pair of edges, but on the empty graph it tests all possible pairs before terminating. Therefore, the query complexity of this algorithm is n(n − 1)/2: in the worst case, the algorithm performs n(n − 1)/2 tests.

The algorithm described above is not the only possible method of testing for non-emptiness, but the Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture implies that every deterministic algorithm for testing non-emptiness has the same query complexity, n(n − 1)/2. That is, the property of being non-empty is evasive. For this property, the result is easy to prove directly: if an algorithm does not perform n(n − 1)/2 tests, it cannot distinguish the empty graph from a graph that has one edge connecting one of the untested pairs of vertices, and must give an incorrect answer on one of these two graphs.

Definitions

In the context of this article, all graphs will be simple and undirected, unless stated otherwise. This means that the edges of the graph form a set (and not a multiset) and each edge is a pair of distinct vertices. Graphs are assumed to have an implicit representation in which each vertex has a unique identifier or label and in which it is possible to test the adjacency of any two vertices, but for which adjacency testing is the only allowed primitive operation.

Informally, a graph property is a property of a graph that is independent of labeling. More formally, a graph property is a mapping from the set of all graphs to {0,1} such that isomorphic graphs are mapped to the same value. For example, the property of containing at least 1 vertex of degree 2 is a graph property, but the property that the first vertex has degree 2 is not, because it depends on the labeling of the graph (in particular, it depends on which vertex is the "first" vertex). A graph property is called non-trivial if it doesn't assign the same value to all graphs. For instance, the property of being a graph is a trivial property, since all graphs possess this property. On the other hand, the property of being empty is non-trivial, because the empty graph possesses this property, but non-empty graphs do not. A graph property is said to be monotone if the addition of edges does not destroy the property. Alternately, if a graph possesses a monotone property, then every supergraph of this graph on the same vertex set also possesses it. For instance, the property of being nonplanar is monotone: a supergraph of a nonplanar graph is itself nonplanar. However, the property of being regular is not monotone.

The big Oh notation is often used for query complexity. In short, f(n) is O(g(n)) if for large enough n, f(n) ≤ c g(n) for some positive constant c. Similarly, f(n) is Ω(g(n)) if for large enough n, f(n) ≥ c g(n) for some positive constant c. Finally, f(n) is Θ(g(n)) if it is both O(g(n)) and Ω(g(n)).

Query complexity

The deterministic query complexity of evaluating a function on n bits (x1, x2, ... ,xn) is the number of bits xi that have to be read in the worst case by a deterministic algorithm to determine the value of the function. For instance, if the function takes value 0 when all bits are 0 and takes value 1 otherwise (this is the OR function), then the deterministic query complexity is exactly n. In the worst case, the first n − 1 bits read could all be 0, and the value of the function now depends on the last bit. If an algorithm doesn't read this bit, it might output an incorrect answer. (Such arguments are known as adversary arguments.) The number of bits read are also called the number of queries made to the input. One can imagine that the algorithm asks (or queries) the input for a particular bit and the input responds to this query.

The randomized query complexity of evaluating a function is defined similarly, except the algorithm is allowed to be randomized, i.e., it can flip coins and use the outcome of these coin flips to decide which bits to query. However, the randomized algorithm must still output the correct answer for all inputs: it is not allowed to make errors. Such algorithms are called Las Vegas algorithms, which distinguishes them from Monte Carlo algorithms which are allowed to make some error. Randomized query complexity can also be defined in the Monte Carlo sense, but the Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture is about the Las Vegas query complexity of graph properties.

Quantum query complexity is the natural generalization of randomized query complexity, of course allowing quantum queries and responses. Quantum query complexity can also be defined with respect to Monte Carlo algorithms or Las Vegas algorithms, but it is usually taken to mean Monte Carlo quantum algorithms.

In the context of this conjecture, the function to be evaluated is the graph property, and the input is a string of size n(n − 1)/2, which gives the locations of the edges on an n vertex graph, since a graph can have at most n(n − 1)/2 possible edges. The query complexity of any function is upper bounded by n(n − 1)/2, since the whole input is read after making n(n − 1)/2 queries, thus determining the input graph completely.

Deterministic query complexity

For deterministic algorithms, Rosenberg (1973) originally conjectured that for all nontrivial graph properties on n vertices, deciding whether a graph possesses this property requires Ω(n2) queries. The non-triviality condition is clearly required because there are trivial properties like "is this a graph?" which can be answered with no queries at all.

The conjecture was disproved by Aanderaa, who exhibited a directed graph property (the property of containing a "sink") which required only O(n) queries to test. A sink, in a directed graph, is a vertex of indegree n-1 and outdegree 0. This property can be tested with less than 3n queries (Best, van Emde Boas & Lenstra 1974). An undirected graph property which can also be tested with O(n) queries is the property of being a scorpion graph, first described in Best, van Emde Boas & Lenstra (1974).

Then Aanderaa and Rosenberg formulated a new conjecture (the Aanderaa–Rosenberg conjecture) which says that deciding whether a graph possesses a non-trivial monotone graph property requires Ω(n2) queries.[1] This conjecture was resolved by Rivest & Vuillemin (1975) by showing that at least n2/16 queries are needed to test for any nontrivial monotone graph property. The bound was further improved to n2/9 by Kleitman & Kwiatkowski (1980), and then to n2/4 + o(n2) by Kahn, Saks & Sturtevant (1983).

Richard Karp conjectured the stronger statement (which is now called the evasiveness conjecture or the Aanderaa–Karp–Rosenberg conjecture) that "every nontrivial monotone graph property for graphs on n vertices is evasive."[2] A property is called evasive if determining whether a given graph has this property requires exactly n(n − 1)/2 queries.[3] This conjecture says that the best algorithm for testing any nontrivial monotone property must query all possible edges. This conjecture is still open, although several special graph properties have shown to be evasive for all n. The conjecture has been resolved for the case where n is prime by Kahn, Saks & Sturtevant (1983) using a topological approach. The conjecture has also been resolved for all non-trivial monotone properties on bipartite graphs by Yao (1988). Minor-closed properties have also been shown to be evasive for large n (Chakrabarti, Khot & Shi 2001).

Randomized query complexity

Richard Karp also conjectured that Ω(n2) queries are required for testing nontrivial monotone properties even if randomized algorithms are permitted. No nontrivial monotone property is known which requires less than n2/4 queries to test. A linear lower bound (i.e., Ω(n)) follows from a very general relationship between randomized and deterministic query complexities. The first superlinear lower bound for this problem was given by Yao (1991) who showed that Ω(n log1/12 n) queries are required. This was further improved by King (1988) to Ω(n5/4), and then by Hajnal (1991) to Ω(n4/3). This was subsequently improved to the current best known lower bound of Ω(n4/3 log1/3 n) by Chakrabarti & Khot (2001).

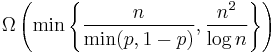

Some recent results give lower bounds which are determined by the critical probability p of the monotone graph property under consideration. The critical probability p is defined as the unique p such that a random graph G(n, p) possesses this property with probability equal to 1/2. A random graph G(n, p) is a graph on n vertices where each edge is chosen to be present with probability p independent of all the other edges. Friedgut, Kahn & Wigderson (2002) showed that any monotone property with critical probability p requires  queries. For the same problem, O'Donnell et al. (2005) showed a lower bound of Ω(n4/3/p1/3).

queries. For the same problem, O'Donnell et al. (2005) showed a lower bound of Ω(n4/3/p1/3).

As in the deterministic case, there are many special properties for which an Ω(n2) lower bound is known. Moreover, better lower bounds are known for several classes of graph properties. For instance, for testing whether the graph has a subgraph isomorphic to any given graph (the so-called subgraph isomorphism problem), the best known lower bound is Ω(n3/2) due to Gröger (1992).

Quantum query complexity

For bounded-error quantum query complexity, the best known lower bound is Ω(n2/3 log1/6 n) as observed by Andrew Yao.[4] It is obtained by combining the randomized lower bound with the quantum adversary method. The best possible lower bound one could hope to achieve is Ω(n), unlike the classical case, due to Grover's algorithm which gives a O(n) query algorithm for testing the monotone property of non-emptiness. Similar to the deterministic and randomized case, there are some properties which are known to have an Ω(n) lower bound, for example non-emptiness (which follows from the optimality of Grover's algorithm) and the property of containing a triangle. More interestingly, there are some graph properties which are known to have an Ω(n3/2) lower bound, and even some properties with an Ω(n2) lower bound. For example, the monotone property of nonplanarity has an Ω(n3/2) lower bound (Ambainis et al. 2008) and the monotone property of containing more than half the possible number of edges (also called the majority function) has an Ω(n2) lower bound (Beals et al. 2001).

Notes

- ^ Triesch (1996)

- ^ Lutz (2001)

- ^ Kozlov (2008, pp. 226–228)

- ^ The result is unpublished, but mentioned in Magniez, Santha & Szegedy (2005).

References

- Ambainis, Andris; Iwama, Kazuo; Nakanishi, Masaki; Nishimura, Harumichi; Raymond, Rudy; Tani, Seiichiro; Yamashita, Shigeru (2008), "Quantum query complexity of Boolean functions with small on-sets", Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Algorithms and Computation, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 5369, Gold Coast, Australia: Springer-Verlag, pp. 907–918, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-92182-0_79, ISBN 978-3-540-92181-3.

- Beals, Robert; Buhrman, Harry; Cleve, Richard; Mosca, Michele; de Wolf, Ronald (2001), "Quantum lower bounds by polynomials", Journal of the ACM 48 (4): 778–797, doi:10.1145/502090.502097.

- Best, M.R.; van Emde Boas, P.; Lenstra, H.W. (1974), A sharpened version of the Aanderaa-Rosenberg conjecture, Report ZW 30/74, Mathematisch Centrum Amsterdam, hdl:1887/3792.

- Chakrabarti, Amit; Khot, Subhash (2001), "Improved Lower Bounds on the Randomized Complexity of Graph Properties", Proceedings of the 28th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages and Programming, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2076, Springer-Verlag, pp. 285–296, doi:10.1007/3-540-48224-5_24, ISBN 978-3-540-42287-7.

- Chakrabarti, Amit; Khot, Subhash; Shi, Yaoyun (2001), "Evasiveness of subgraph containment and related properties", SIAM Journal on Computing 31 (3): 866–875, doi:10.1137/S0097539700382005.

- Friedgut, Ehud; Kahn, Jeff; Wigderson, Avi (2002), "Computing Graph Properties by Randomized Subcube Partitions", Randomization and Approximation Techniques in Computer Science, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2483, Springer-Verlag, p. 953, doi:10.1007/3-540-45726-7_9, ISBN 978-3-540-44147-2.

- Gröger, Hans Dietmar (1992), "On the randomized complexity of monotone graph properties", Acta Cybernetica 10 (3): 119–127, http://www.inf.u-szeged.hu/actacybernetica/edb/vol10n3/pdf/Groger_1992_ActaCybernetica.pdf.

- Hajnal, Péter (1991), "An Ω(n4/3) lower bound on the randomized complexity of graph properties", Combinatorica 11 (2): 131–143, doi:10.1007/BF01206357.

- Kahn, Jeff; Saks, Michael; Sturtevant, Dean (1983), "A topological approach to evasiveness", 24th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (sfcs 1983), Los Alamitos, CA, USA: IEEE Computer Society, pp. 31–33, doi:10.1109/SFCS.1983.4, ISBN 0-8186-0508-1.

- King, Valerie (1988), "Lower bounds on the complexity of graph properties", Proc. 20th ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Chicago, Illinois, United States, pp. 468–476, doi:10.1145/62212.62258, ISBN 0897912640.

- Kleitman, D.J.; Kwiatkowski, DJ (1980), "Further results on the Aanderaa-Rosenberg conjecture", Journal of Combinatorial Theory. Series B 28: 85–95, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(80)90057-X.

- Kozlov, Dmitry (2008), Combinatorial Algebraic Topology, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 9783540730514.

- Lutz, Frank H. (2001), "Some results related to the evasiveness conjecture", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 81 (1): 110–124, doi:10.1006/jctb.2000.2000.

- Magniez, Frédéric; Santha, Miklos; Szegedy, Mario (2005), "Quantum algorithms for the triangle problem", Proceedings of the sixteenth annual ACM-SIAM symposium on Discrete algorithms, Vancouver, British Columbia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, pp. 1109–1117, arXiv:quant-ph/0310134, http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1070591.

- O'Donnell, Ryan; Saks, Michael; Schramm, Oded; Servedio, Rocco A. (2005), "Every decision tree has an influential variable", Proc 46th IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 31–39, doi:10.1109/SFCS.2005.34, ISBN 0-7695-2468-0.

- Rivest, Ronald L.; Vuillemin, Jean (1975), "A generalization and proof of the Aanderaa-Rosenberg conjecture", Proc. 7th ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States, pp. 6–11, doi:10.1145/800116.803747.

- Rosenberg, Arnold L. (1973), "On the time required to recognize properties of graphs: a problem", SIGACT News 5 (4): 15–16, doi:10.1145/1008299.1008302.

- Triesch, Eberhard (1996), "On the recognition complexity of some graph properties", Combinatorica 16 (2): 259–268, doi:10.1007/BF01844851.

- Yao, Andrew Chi-Chih (1988), "Monotone bipartite graph properties are evasive", SIAM Journal on Computing 17 (3): 517–520, doi:10.1137/0217031.

- Yao, Andrew Chi-Chih (1991), "Lower bounds to randomized algorithms for graph properties", Journal of Computer and System Sciences 42 (3): 267–287, doi:10.1016/0022-0000(91)90003-N.

Further reading

- Laszlo Lovasz; Young, Neal E. (2002). "Lecture Notes on Evasiveness of Graph Properties". arXiv:cs/0205031v1 [cs.CC].

- Chronaki, Catherine E (1990), A survey of Evasiveness: Lower Bounds on the Decision-Tree Complexity of Boolean Functions, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.37.1041, retrieved 2009-10-10.

- Michael Saks. "Decision Trees: Problems and Results, Old and New". http://www.math.rutgers.edu/~saks/PUBS/dtsurvey.pdf.